AI: Pandora’s Box or Innovation

Finding a balance between solving the new questions AI raises and the benefits of innovation

There are two huge issues related to AI and intellectual property. One is its use of content. The user enters content in the form of a prompt on which the AI performs some action. What happens to that content after AI responds? The other is AI’s creation of content. AI uses its algorithms and knowledge base of training data to respond to a prompt and generate output. Considering the fact that it has been trained on potentially copyrighted material and other intellectual property, is the output novel enough to copyright?

AI’s use of intellectual property

It seems like AI and ChatGPT are in the news everyday. ChatGPT, or Generative Pre-trained Transformer, is an AI chatbot launched late 2022 by OpenAI. ChatGPT uses an AI model that has been trained using the internet. The non-profit company, OpenAI, currently offers a free version of ChatGPT which they call the research preview. “The OpenAI API can be applied to virtually any task that involves understanding or generating natural language, code, or images. “ (Source). In addition to using ChatGPT as an open ended conversation with and AI assistant (or, Marv, a sarcastic chat bot that reluctantly answers questions), it can also be used to:

- Translate programming languages – Translate from one programming language to another.

- Explain code – Explain a complicated piece of code.

- Write a Python docstring – Write a docstring for a Python function.

- Fix bugs in Python code – Find and fix bugs in source code.

The rapid adoption of AI

Software companies are scrambling to integrate AI into their applications. There is a cottage industry around ChatGPT. Some create applications that leverage its APIs. There is even one website that bills itself as a ChatGPT prompt marketplace. They sell ChatGPT prompts!

Samsung was one company that saw the potential and jumped on the bandwagon. An engineer at Samsung used ChatGPT to help him debug some code and help him fix the errors. Actually, engineers on three separate occasions uploaded corporate IP in the form of source code to OpenAI. Samsung allowed – some sources say, encouraged – its engineers in the semiconductor division to use ChatGPT to optimize and fix confidential source code. After that proverbial horse was invited out to pasture, Samsung slammed the barn door shut by limiting content shared with ChatGPT to less than a tweet and investigating the staff involved in the data leak. It’s now considering building its own chatbot. (Image generated by ChatGPT – a potentially unintentionally ironic, if not humorous, response to the prompt, “a team of Samsung software engineers using OpentAI ChatGPT to debug software code when they realize with surprise and horror that the toothpaste is out of the tube and they have exposed corporate intellectual property to the internet”.)

Classifying the security breach as a “leak” may be a misnomer. If you turn on a faucet, it’s not a leak. Analogously, any content you enter in OpenAI should be considered public. That’s O-P-E-N A-I. It’s called open for a reason. Any data you enter in ChatGpt may be used “to improve their AI services or might be used by them and/or even their allied partners for a variety of purposes.” (Source.) OpenAI does warn users in its user guide: “We are not able to delete specific prompts from your history. Please don’t share any sensitive information in your conversations,” ChatGPT even includes a caveat in its responses, “please note that the chat interface is intended as a demonstration and is not intended for production use.”

Samsung is not the only company releasing proprietary, personal and confidential information into the wild. A research company found that everything from corporate strategic documents to patient’s names and medical diagnosis had been loaded into ChatGPT for analysis or processing. That data is being used by ChatGPT to train the AI engine and to refine the prompt algorithms.

Users mostly don’t know how their sensitive personal identifying information is managed, used, stored or even shared. Online threats and vulnerabilities in AI chatting are significant security issues if an organization and its systems are compromised, the personal data is leaked, stolen and used for malicious purposes.

The nature of AI chatting is to process and analyze a large amount of data, including personal information, to produce relevant results. However, the use of big data seems to diverge from the concept of privacy…(Source.)

This is not an indictment of AI. It’s a reminder. It’s a reminder that AI should be treated like the internet. In other words, consider any information you feed into OpenAI as public. (Remember, too, that any output generated by AI can be further transformed or used as a model to generate answers for future users.) It’s one way in which AI compromises intellectual property and privacy. Another controversy is AI’s use of copyrighted material.

AI and the copyright dilemma

There are a number of concerns related to AI fair use and copyrighted material. AI is capable of processing the written word. It can summarize, analyze, categorize and even create new content based on a particular writing style. AI is trained on content. I think it would be hard for it to avoid consuming copyrighted material. As far as I know, current law does not fully address the use of copyrighted content for training. (Image)

I asked OpenAI to type the text for the first page of “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee. It did. So, I’m pretty sure that it has access to the copyrighted text. It can then create a resume in the style of Harper Lee. Or, you can ask it to create a sonnet based on the theme of the book.

| A Shakespearean Sonnet

Based on the Theme of “To Kill a Mockingbird” In Maycomb’s town where justice seems a dream, Young Scout and Jem find truth beyond their years. Their father, Atticus, a noble theme Whose moral compass guides them through their fears. Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused, Denied a voice, a trial that’s just and fair. But Atticus defends him, not amused, For truth and justice must be our affair. The mockingbird, a symbol of pure grace, Innocent of harm, its song brings peace. But evil lurks within this small town’s space, And justice falls as hate begins to increase. Harper Lee’s words, a warning to us all, To fight for justice, lest it be our fall. |

|---|

There’s no chance that this will be mistaken with Shakespeare’s work – or Harper Lee’s for that matter. It is transformational new content clearly not to be confused with the original. Several questions arise. At what point does it become transformational? In other words, how much does the original work need to be changed for it to be considered new content?

Another question – and this applies equally to any content created by AI – who owns it? Who owns the copyright to the content? Or, can the work even be copyrighted? An argument can be made that the owner of the copyright should be the individual who crafted the prompt and made the request of OpenAI. There is a new cottage industry around prompt authoring. On some online marketplaces, you can pay between $2 and 20 for prompts that will get you computer generated art or written text.

Others say it should belong to the developer of OpenAI. That raises still more questions. Does it depend on the model or engine that is used to generate the response?

I think the most compelling argument to be made is that content generated by a computer cannot be copyrighted. The US Copyright Office issued a statement of policy in the Federal Register, March 2023. In that, it states, “Because the Office receives roughly half a million applications for registration each year, it sees new trends in registration activity that may require modifying or expanding the information required to be disclosed on an application.” It goes on to say, “These technologies, often described as ‘generative AI,’ raise questions about whether the material they produce is protected by copyright, whether works consisting of both human-authored and AI-generated material may be registered, and what information should be provided to the Office by applicants seeking to register them.”

“The Office” acknowledges that there are questions related to applying a 150-year old law to technology that hasn’t seen its first birthday. To address those questions, the Copyright Office launched an initiative to study the issue. It is going to research and open to public comment on how it should address the use of copyrighted content in the training of AI, as well as, how it should consider the content that is generated.

The Federal Register, somewhat surprisingly, offers some color commentary and describes a number of interesting cases related to the “authorship” of works and its historical policies on copyright. One case that was adjudicated held that a monkey cannot hold a copyright. In this particular case, monkeys captured images with a camera. The court ruled that the images could not be copyrighted because the Copyright Act refers to an author’s ‘‘children,’’ ‘‘widow,’’ ‘‘grandchildren,’’ and ‘‘widower.” In the court’s eyes, this language excluded monkeys. “The Office’s existing registration guidance has long required that works be the product of human authorship.”

When OpenAI is asked about the controversy, it says, “Yes, there are gray areas of intellectual property law when it comes to software and AI. Because of the complexity of the technology and the lack of established legal precedents, it is often difficult to determine what rights a creator has to their work. For example, if an AI algorithm is based on a novel or an existing software program, it is not always clear who owns the rights to the algorithm or the original work. Additionally, the scope of patent protection for AI-related inventions is a contentious legal issue.”

OpenAI is right on this. It is clear that a US application for copyright must have human authorship. Between now and the end of the year, the Copyright Office will attempt to sort out some of the remaining questions and provide additional guidance.

Patent Law and AI

Discussions around US Patent Law and whether it covers inventions made by AI is a similar story. Currently, as the law is written, patentable inventions must be made by natural persons. The US Supreme Court refused to hear a case that challenged that notion. (Source.) Like the US Copyright Office, the US Patent and Trademark Office is evaluating its position. It is possible that the USPTO decides to make intellectual property ownership more complex. The AI creators, developers, owners may own part of the invention it helps to create. Could a non-human be part owner?

The tech-giant Google weighed in recently. “‘We believe AI should not be labeled as an inventor under the U.S. Patent Law, and believe people should hold patents on innovations brought about with the help of AI,’ Laura Sheridan, senior patent counsel at Google, said.” In Google’s statement, it recommends increased training and awareness of AI, the tools, the risks, and best practices for patent examiners. (Source.) Why doesn’t the Patent Office adopt the use of AI to evaluate AI?

AI and the Future

The capabilities of AI and, in fact, the entire AI landscape has changed in just the last 12 months, or so. Many companies want to leverage the power of AI and reap the proposed benefits of faster and cheaper code and content. Both business and the law need to have a better understanding of the implications of the technology as it relates to privacy, intellectual property, patents and copyright. (Image generated by ChatGPT with human prompt “AI and the Future”. Note, image is not copyrighted).

Update: May 17, 2023

There continue to be developments related to AI and the law every day. The Senate has a Judiciary Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law. It is holding a series of hearings on Oversight of A.I.: Rule for Artificial Intelligence. It intends “to write the rules of AI.” With the goal “to demystify and hold accountable those new technologies to avoid some of the mistakes of the past,” says chairman of the subcommittee, Sen. Richard Blumenthal. Interestingly, to open the meeting, he played a deep fake audio cloning his voice with ChatGPT content trained on his previous remarks:

Too often, we have seen what happens when technology outpaces regulation. The unbridled exploitation of personal data, the proliferation of disinformation, and the deepening of societal inequalities. We have seen how algorithmic biases can perpetuate discrimination and prejudice and how the lack of transparency can undermine public trust. This is not the future we want.

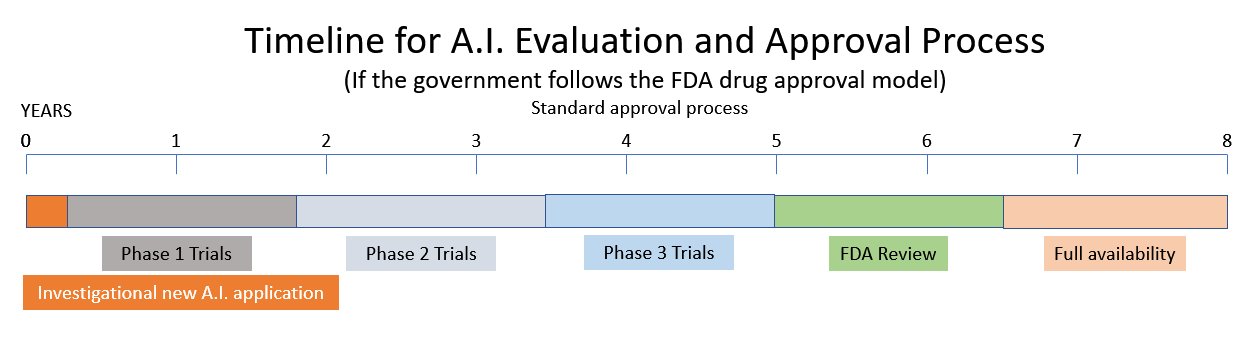

It is considering a recommendation to create a new Artificial Intelligence Regulatory Agency based on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) models. (Source.) One of the witnesses before the AI subcommittee suggested that AI should be licensed similarly to how pharmaceuticals are regulated by the FDA. Other witnesses describe the current state of AI as the Wild West with dangers of bias, little privacy, and security issues. They describe a West World dystopia of machines that are “powerful, reckless and difficult to control.”

To bring a new drug to market takes 10 – 15 years and half a billion dollars. (Source.) So, if the Government decides to follow the models of the NRC and FDA, look for the recent tsunami of exciting innovation in the area of Artificial Intelligence to be replaced in the very near future by government regulation and red tape.